Whether your goal is to avoid checked or excess bag fees by packing light or simply make sure you take everything you need on your next vacation, here are our top 10 tips for packing for a cruise.

Tip 1: Pack your carry-on bags wisely.

Pack a change of clothes and important meds or toiletries in the bags you will take on the plane and personally transport onboard. This is important for two reasons: First, if your luggage gets lost by the airline on the way to your cruise, at least you’ll have some essentials with you. It can take a while for your luggage to be found and then shipped to the next port of call. Second, in case your suitcases are delayed in being delivered to your cabin, you’ll have a bathing suit or dinner attire on hand and can enjoy all the onboard activities right away, rather than waiting for your bags to show up.

Tip 2: Pack your checked luggage wisely.

Be smart about your checked bags, too. If you tend to overpack, lay out all the clothes you think you’ll need, then only pack half the clothing and three-quarters of the shoes. To save space, roll your clothes rather than fold them. Finally, never pack valuables in your checked bags, as they could be stolen. Carry all cameras, electronic games, jewelry and prescription medicine in your carry-on.

Tip 3: Know the dress codes.

While some folks still dress to the nines (formal gowns and tuxedos) for ships’ formal nights, most people dress more informally (suits for men and cocktail garb – flowing pantsuits or little black dresses – for women). “Resort casual” is now the ubiquitous evening dress; think date night, with men in slacks and buttoned shirts (no jackets) and women in everything from sundresses to skirts or slacks with cute tops. Even jeans are now a staple in many cruise ship dining rooms.

Tip 4: Consider doing laundry onboard.

If you want to pack light, consider having your laundry done onboard. Cruises usually offer laundry services for a reasonable cost, and if this helps keep your checked bag cost down, you may end up saving even more. You can always save on laundry costs by bringing travel detergent and rinsing out underwear and shirts in your cabin’s bathroom, or packing a bottle of travel-sized Febreze to get one more day’s use out of a gently worn outfit.

Tip 5: Don’t assume your favorite toiletries will be in your cabin.

You’ll uaually find basic toiletries onboard, such as soap and shampoo. In main cabins on some cruise lines, toiletries offered are limited (in some cases to pump bottles of mystery soap affixed to the shower wall). You might want to make room in your luggage for your favorite brands. Same goes for hair dryers. Most staterooms come with weak dryers, so if you’re picky, pack your own. Another tip: Never unpack your toiletry kit. Leave it filled with travel-sized bottles and an extra toothbrush or razor. When it’s time for your next cruise, all you need to do is top off or replace the bottles – rather than wasting time collecting items and possibly forgetting something.

Tip 6: Dress for your destination.

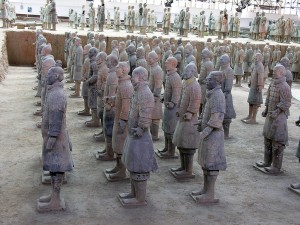

Simply put, some places are more formal than others. Expect to pack more resort-casual wear if traveling to Europe or Bermuda. Other cruise itineraries, such as Hawaii, the Mexican Riviera, the Caribbean and French Polynesia, are more casual than the norm. And don’t forget to think about your in-port activities. Flip-flops are fine for a beach day, but you’ll want more comfortable shoes for long days of sightseeing or active excursions like hiking or biking. If you’re visiting religious sites, you’ll want modest clothing that covers your shoulders and knees, even if it’s quite hot.

Tip 7: Save some room in your suitcase.

You’ll likely pick up at least a few souvenirs during your cruise, so you’ll need room in your luggage to bring them home. Whether you’re picking up leather goods in Italy, Aloha-wear in Hawaii or duty-free goods in the Caribbean, consider packing a foldable duffle. It won’t take up much space in your suitcase, and you can fill it up and check it for the flight home.

Tip 8: Mix and match.

If you can make your clothes do double duty, you won’t be hit with excess bag fees or find yourself fighting for the last hanger in the cabin’s small closet. Stick with one color theme so you can re-wear bottoms with different tops, or bring shirts that can be dressed up for dinner on one night and worn sightseeing the next. Opt for the layered look to handle differing temperatures in the various cruise ports. Change up the look of one formal outfit with different accessories (jewelry, ties, scarves), rather than bring two suits or cocktail dresses. Your shipmates won’t know (or care) if you wear the same outfit twice.

Tip 9: Remember the basics.

Most cruise ship cabins don’t come with alarm clocks, so bring your own. If you’re using your cell phone for this job, put it in airplane mode so you don’t incur roaming charges in foreign waters. Other items you might want to pack because they’re not provided or super-expensive to buy onboard include: over-the-counter meds, batteries, camera memory cards, sunscreen, ear plugs, plastic bags for transporting liquids or wet things (or keeping water out of your gear on water-based tours) and power strips to charge all your electronics.

Tip 10: Keep all important documents with you.

Always make sure you bring your necessary IDs and documents – and never pack them in your checked luggage. You’ll want your photo ID and cruise ship boarding pass on hand, so even if your suitcase misses the boat, you can get onboard. Make sure you have the correct type of identification for your cruise destination, whether it’s a passport or birth certificate and photo ID. Wannabe cruisers have been turned away from the pier for having just a copy of their birth certificate (and not the required original) or a passport with a name that doesn’t match the one on the ship’s manifest. If you need visas or immunizations for your cruising region, carry those documents with you, as well.

Edited from Cruise Critic